When Did You First Notice That Middle-Age Had Conquered Your Face?

I was blind. Until suddenly, I saw nothing but the drooping skin dangling over my eyes.

While my peers have been injecting Botox and getting other anti-aging procedures, I’ve taken a hands-off approach to middle-age. This is not because I’m aging well (my mother, in my opinion, looks younger than me), and it’s also not because I’ve mastered the art of maturing with grace.

The truth is that when I started looking old, I simply didn’t notice.

I was living my life, completely unaware of the changes happening right before my eyes. To my eyes.

It’s not as if I’m totally oblivious. When my husband, Tomer, started to go gray, I took notice. He’s rocking the salt-and-pepper look now. Smiling causes crinkles around his eyes and mouth. He even has some white hairs sprouting from his neck.

I see him every day, so from my perspective, Tomer is aging gradually, and my mind registers said changes along the way.

But with my own face, I completely missed the transformation.

If Tomer’s face is like the rock that slowly withers in the wind, my youth disappeared by way of an avalanche. At least, this is how it seemed to me. I was blind to change until someone pointed it out, and even then, it took another several hours for me to see it.

The triggering incident happened at a summer barbecue. We were traveling out of state and visited some friends we hadn’t seen in awhile. Within minutes of our arrival, our host, Nancy, handed me a beverage. As I thanked her, I watched her mouth drop.

“Your eyes,” she exclaimed. “I mean, mine are getting droopy too, but yours are seriously hooded.”

I didn’t know what she meant by “hooded eyes.” Later, I would Google it. In the meantime, Nancy could not hide her horror. I understood that my situation was serious.

“You need surgery. It’s called a blepharoplasty,” Nancy said.

I must’ve looked uncomfortable, because then she started apologizing.

“It’s just that you always had such a beautiful face. It’s a shame to let it go. We all need to do stuff now, to keep our looks.” Nancy pointed at her forehead and recommended Botox injections too. “It takes years off.”

I excused myself and headed for the restroom where I initiated a days-long investigation of my hooded eyelids. I turned on all the light switches, but still, I didn’t see the excess skin dangling over my pupils. I leaned up against the mirror. I tried it with my readers on. Nothing. If I was suffering from hooded eyes, then I was probably also suffering from age-related vision loss. I saw no droop. My eyes looked like they’ve always looked.

Later that night, we returned to my sister-in-law’s home where we were staying for the week. Natalie brought a handheld mirror to the family room. She held it. I gazed at my face.

“I don’t see the hoods,” I said.

At this point, everyone from my children to my spouse could locate said hoods. Tomer tried to comfort me. He’d Googled “hooded eyes” and told me to be proud because “even Jennifer Lawrence has them.”

My kids had had enough.

Natalie was growing exasperated too. “This isn’t like you to fixate on your appearance like this. Who cares if you have hooded eyes?”

But nobody was understanding the source of my distress. It wasn’t that I was upset with my appearance. It was that I couldn’t see it. Of course, if I’d been able to see it, I might’ve been upset about my aging eyelids too.

Plus, my concern wasn’t limited to the aesthetic. While Googling blepharoplasty, I learned that the surgery is sometimes used to treat visual obstruction. That if my eyelids kept falling, they’d be less like hoods and more like window shades and I wouldn’t be able to see through them and would I lose my driver’s license?

I was devastated for my blind future. And I was devastated that I couldn’t see the reality of my face in the present moment either.

Natalie handed me the mirror for the tenth time. I gazed again. Nothing.

“I see the problem,” she said. “You’re raising your eyebrows when you look at yourself.”

“What are you talking about? I’m not raising anything.”

Tomer interjected. “Yeah, you always do that when you look in the mirror.”

“Do what?”

“Raise your eyebrows. I mean, you kind of live life with a lot of eyebrow-raised expression upon your face. Like, in general.”

“Well that solves it then,” Natalie said. “Every time you look in the mirror, your eyebrows are raised, so you don’t see the hooded lids. Your facial expression is performing an eye lift.”

She made me relax and stuck the mirror in front of my face again.

And that’s when the avalanche began to tumble. Under my relaxed brows, I saw reality for the first time. It was shocking to see myself so suddenly. Woe.

Who the fuck is that?

I wondered.

And then came another devastating revelation.

Holy shit. My mother was right.

Memories hurled straight at me. With terrible clarity, I recalled all the instances I’d argued with my mother through the years. Whenever she complained about her aging appearance, I shrugged and said that people—especially women—should embrace their aged faces. It was a gift and a privilege to still be alive. We needed to fight the patriarchy, uphold feminist ideals, and celebrate the inevitable sag.

But Mom warned me. “You don’t know how you’re going to feel when you look in the mirror someday.”

“No way.” I shook my head. “I’m going to feel great even if I end up looking like an old hag. And I’m not going to waste my one wild and precious life seeking the fountain of youth.”

I had higher goals.

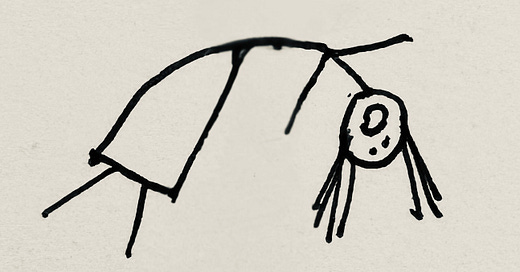

What I imagined for myself by age fifty was a middle-aged renaissance. Having acquired decades of wisdom and talent, I’d be traveling the world, enjoying fine dining, and painting works of art. I really wanted to learn how to draw and sculpt someday.

I never saw this plot twist coming:

Artist: Jen Gilman Porat, Age 50

Self-Portrait

Time corrects all kinds of snobbery.

I had no empathy for older women when I was twenty-five. I judged any preoccupation with an aging epidermis as a moral failure. I tried to relate, but whenever I imagined myself at age 50, I looked 25. My mind’s eye lacked an old age filter.

I didn’t know it then, but I’d already found the fountain of youth—in my imagination.

If Mom thought I was being stubborn, she didn’t say; however, she took opportunities to further educate me.

According to Mom, what made someone attractive in youth (i.e. good bone structure) doesn’t matter later on. Mature beauty depends on three essential features:

Skin

Hair

Teeth

“When you get older,” Mom said, “the people with the prettiest faces can turn ugly fast. Good cheekbones mean nothing if your skin looks like crepe paper. And if you go bald, nobody notices your pretty smile. And if you lose your teeth, you won’t even have that.”

“Well thank goodness for oral surgeons,” I said. “Isn’t that what dental implants are for?”

Mom raised her eyebrows. “See, you’re already considering surgical interventions.”

I argued that teeth were a necessity that transcended mere beauty. Especially for anyone averse to liquid diets. Then again, I was pretty sure my mother-in-law had already had her teeth done, and she rarely ate a thing. Her diet, to this day, consists of little more than hot water with lemon.

And my mother-in-law didn’t just fear her own weight gain. She feared it for me too. A month before a family wedding back in 2003, when I wasn’t yet 30 and still weighed less than 130 pounds but had crept over the 120 pound line, she’d warned me.

“It doesn’t matter how pretty you are if you get fat,” she said.

As a polar responder, I started to eat more. I resented the pressure to stay tiny. I didn’t like hot water with lemon. I upped my caloric intake.

It felt like a revolution. A non-violent resistance. I would never succumb!

Of course, all my feminist intention crumbled in front of my hooded-eyes that summer evening. I wasn’t feeling great. I was mourning the loss of my youthful eyelids.

I started reading up on blepharoplasty. I wondered if I should schedule a surgical consult. Then, I read that my hypothyroidism and dry eyes made me a poor candidate for the procedure. Panic set in. What if the hoods really started to obstruct my vision? Would I need to wear something akin to a miniature bra made for eyelids?

It was all too much. I needed to reaffirm my goals.

Was it too late to take drawing classes? Could I still learn to manage something more than a stick figure?

I complained to friends. I said I wanted to be interesting. Not sewn and tucked. Someone scolded me.

“You can’t judge women who seek surgical intervention,” she said. “That’s not very feminist of you. Women need to support other women however they choose to age.”

I struggled with this.

I’ve had to go under the knife for medical reasons, and it seemed both selfish and futile to chase youth. Why risk one’s life with elective procedures? None of us are getting out of here alive anyway. Then again, maybe we should try and look great while we’re still here?

I remembered that even if I wanted to opt for surgery, I wasn’t a candidate for an eye job. Even if I wanted to enter the race, I’m not eligible to compete.

“There’s no way out of my drooping eyelids,” I complained to Tomer. “I guess I’ll invest in some cool sunglasses and a boob job. I’ll hide my eyes and redirect attention elsewhere.”

“I hate fake boobs,” he said. “They have no give. No bounce.”

I had to agree. But what if mine ended up hanging beneath my belly button? I heard Mom’s voice again: You don’t know how you’re going to feel someday.

And I knew she was right. Would I run for a surgical consult or fling those boobs over my shoulders with a fuck it attitude?

As for Tomer, I caught him trying to comb hair over a bald spot the other day. I’d assumed that men don’t grapple with age-related changes to their appearance, and it turns out I was wrong about this too.

“Both my dad and my grandpa went bald,” he said. “I’m trying to enjoy the hair I have while it’s still here.”

I tried to imagine my husband without any hair, but I couldn’t. My mind’s eye still lacks the old-age filter. Maybe if I had developed more artistic talents, I’d be able to picture things with more accuracy? But even if I could, what would I want to see?

I wonder.

I wonder if I’ve been too rigid in my thinking, imagining myself torn between two extremes: that of gray-haired crone versus plastic wanna-be Barbie.

How does a middle-aged woman hold onto more nuance despite her rapidly shifting looks?

I laughed out loud reading this entire piece and it is so spot on. My husband has made fun of how I do a Duck Face when I look in the mirror - I never noticed, but apparently I am *always* sucking in my cheeks. A habit I picked up very young, like before I got to preschool, because even then - like you MIL - the need to be skinny was baked into the mashed potatoes I smashed into my face sitting in my high chair. I try very hard not to judge people who are proactive against aging. BUT - there is a real cognitive dissonance that occurs when I see a disorganized face that has been beaten into submission with botox and surgeries. It's disorienting. The MOST disorienting is when people fuck with their eyes, Jen. I get this weird feeling like there's something wrong and can't put my finger on what it is, and then I realize it's that they've had an eye lift. Embrace the hoods! They're there for your PROTECTION. By the time we hit 50, we've seen some shit. No need to see any more.

The fifties are sort of like adolescence - we transition into older women. Like adolescence it can be rough. I guarantee you’ll look back on yourself in your fifties with amazement at your beauty. In our sixties we hit our stride, come into our own - full expression. I just turned 70 and it’s the first year I’ve been concerned about my looks - it’s the sagging face that gets me - the jowls not the wrinkles which aren’t bad. I too judged older women in my twenties. Ha! Great piece, Jen!